FIFAI

By Eshaan Lumba, Kenneth Ochieng, Jett Bronstein and Aidan Garton

Abstract

Attempts to accurately predict the outcomes of Premier League soccer matches have historically drawn interest from various soccer stakeholders such as sponsors, avid fans, gamblers, and investors. Match predictions are often made using possible odds for or against teams. The most popular odds today are created mainly from statistical methods i.e the poisson distribution, pooled bookie opinions, and other probabilistic methods. Only a few recent ones have been created using neural network models. In this paper, we trained a neural network model using available Premier League data from the 2014/2015 season to the 2021/2022 season, and achieved 81.65% accuracy in predicting a win, loss or draw for future matches. We implemented the model using FastAI and made use of a team’s key datapoints including cumulative win streaks, home goals/away goals, whether the team played at their home field, and the match referee. We recognize, however, that our model can unintentionally propagate negative social impact by encouraging compulsive gambling or diminishing the thrill of watching Premier League matches with 70% - 80% accurate pre-match predictions.

Keywords: soccer outcome prediction, neural network, deep learning, EPL, gambling

Introduction

The English Premier League is considered one of the most exciting soccer leagues in all of the world making Premier League games some of the most watched cable events in the world. Like other mainstream sporting leagues, the Premier League attracts significant attention from the gambling industry. Currently, predicting the victor of a Premier League match with high certainty is very difficult. We will attempt to construct a comprehensive neural network to successfully predict the result of Premier League matches on a consistent basis.

To improve upon the previous results, we will try to use a more robust dataset with different datapoints along with a more optimized algorithm and model. Another key modification is that previous results are outdated (up to 2018), whereas we want to keep our model as up to date as possible. This would mean utilizing a dataset that includes the latest games from the ongoing 2021-2022 season.

Ideally, we would like to have an algorithm that can accurately predict the result upwards of 70% of the time. Though this is about 10% lower than the current best, we feel as though it would be an appropriate challenge for us to be close to that level of accuracy given that our model is not too complicated, and we will not be including too large a set of datapoints. A key challenge is understanding which datapoints have the biggest correlation with a match’s outcome. This is difficult to predict beforehand and thus we will adjust our model through trial and error to improve the algorithms as much as possible.

We acknowledge that predicting the result of a Premier League match is a very difficult problem, but we hope to succeed in improving on previous results if possible. Ultimately, we would like to test our data on the current set of ongoing premier league matches to determine the success rate of our algorithm. A lot of factors can change as teams change throughout the season, but we hope to build a model capable of making predictions at a sufficiently consistent rate.

Related Works

Due to the high demand and market for sports betting and the surrounding fan anticipation/engagement, there have been several previous studies on the prediction of sporting events using neural networks. While much of the work produced to predict soccer outcomes has been adapted from the prediction of other sporting events, such as those of NBA and NFL games, the following papers have provided essential and extensive background knowledge on our topic for soccer matches, some of which focus entirely on the English Premier League, just as we do in our study. Here, we outline the main contributions of these works and explain the nuances and points of expansion that our study focuses on.

The primary source and motivation for our project comes from a study done by Sarika et al. titled “Soccer Result Prediction Using Deep Learning and Neural Networks”. This study compares several different prior sport outcome predictors and constructs their own in the form of an RNN (recurrent neural network). Using data from the 2011-2017 seasons of the EPL, Sarika and his colleagues trained their model to accurately predict EPL match outcomes up to 80% of the time. Sarika and his team used LSTM (long, short-term memory) cells composed of three gates: forget gates, input gates, and output gates. We use this architecture as our main source of motivation to produce an even higher accuracy model for EPL game outcomes.

Another key piece of research for our project comes from Wagenaar et al. in their paper “Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks to Predict Goal-scoring Opportunities in Soccer”. This paper uses two-dimensional image data to predict the chance of a goal-scoring opportunity based on the location of the ball and players relative to each other and each team’s goal. By using a CNN architecture, Wagenaar and his team were able to accurately predict the chance of a goal being scored given a snapshot of the field 67.1% of the time. Notably, this paper uses training data from the Bundesliga, but it still provides pertinent and helpful information on how snapshots of game positions might aid the prediction of overall soccer match score-lines and outcomes as we aim to improve upon with our study.

Predicting soccer games using neural nets is still a relatively niche field and remains mostly under researched. We found one example of a statistical method done by Benedikt Droste in his article, “Predict soccer matches with 50% accuracy”, using the Poisson distribution and the Poisson Regression in python. He first created a Poisson distribution to fit farely well with most of the match results in the 2018 -2019 premier league season and proceeded to predict the results of the last 10 matches of the same season using the Poisson Regression. The predictions achieved a near 50% accuracy. To enhance the predictions, the regression took into account key datapoints for each team such as the likelihood that they would score, the likelihood that they would concede and the likelihood that they would score if they were a home or away team. Moreover, the author suggests looking into more datapoints such as team form, more matches and correctness of under/over underestimating results to make it better. Similarly, with an attention to key match factors, we found a 2018 research paper titled “Football Match Statistics Prediction using Artificial Neural Networks”, by Sujatha et al, where they argue that for any two teams in contention, correctly predicting the outcome of a match involves paying attention to key factors including current team league rank, league points, the UEFA coefficient, home and away goals scored/conceded, team cost, home wins/loses, away wins/loses, home advantage etc. In their research, they pit two Bundesliga teams (Bayern Munich and Dortmund) against each other, and trained a neural network with inputs for each team based on the key factors. They were able to predict outcomes of multiple matches between the two teams with relatively high accuracy (percentages not provided) and in some cases did better when compared to bookie odds.

From our research, we note that neural nets generally do better than available statistical methods in predicting match outcomes. Given the availability of a large volume of premier league data, we plan on coming up with a proper classification of key datapoints and training a neural net that can predict a winning team with a provided confidence percentage.

Methods

For our model, we decided to use a fully-connected Neural Network using FastAI. We deviated from our original plan of using an RNN with LSTM. Past researchers have already built an RNN with LSTMs and they had a few more datapoints than we had access to. Though we initially planned to use a combination of PyTorch and FastAI, we felt that, given our tabular data, it would be best to benefit from the best practices already implemented in the fully connected learning models built by FastAI on top of PyTorch.

We had also discussed building models for each team rather than a one-fits-all approach. For this, we would have 20 or so different models (one for each Premier League team). When predicting the result of a match between two teams, we would get predictions from the home and away team’s model, and then compare the predictions in order to output one final result prediction. However, as we gathered the data and started building the project, we felt that this was unnecessary, as it would be equivalent to simply building one model that took in all of the data, instead of having the 20 or so separate models for each team. It would also allow us to spend less time training the individual models.

For our model, we gathered English Premier League data from the “Football-Data” dataset from the last 8 seasons (including the data from the first half of the current 2021 season). However, we did not use all the datapoints from the dataset. We used the datapoints for a specific game that one could know beforehand. We did this because this would allow us to predict the model. Hence, we did not consider match statistics such as shots, or yellow cards in our model. If we wanted to predict a game between two random teams, we would not have these datapoints available to us before the match, so we did not feel that they would be useful to train on for our immediate purposes. Instead, we gathered the following columns of data from the dataset:

- HomeTeam (The team that was playing at home)

- AwayTeam (The team that was playing away)

- Referee (The referee for the game)

- Results (Our dependent variable: whether the Home Team won, draw, or lost)

- B365H (Betting odds from Bet365 for the home team win)

- B365D (Betting odds from Bet365 for a draw)

- B365L (Betting odds from Bet365 for the home team loss)

- BWH (Betting odds from Bet&Win for the home team win)

- BWD (Betting odds from Bet&Win for a draw)

- BWL (Betting odds from Bet&Win for the home team loss)

Note that the last 6 datapoints from above are essentially betting odds for the result of a game from two different betting companies chosen randomly from the dataset. In addition to the variables taken from the dataset, we also made some of our own calculations and added to the dataset. We added the following datapoints to the dataset:

- HomeWinStreak (The current winning streak of the home team)

- AwayWinStreak (The current winning streak of the away team)

- TGSH (Whether the home team was on a winning streak or not)

- TGSA (Whether the away team was on a winning sreak or not)

Ultimately, these datapoints proved to be the most valuable in determining the result of a game. The motivation behind our creation of these datapoints was from past researchers who had achieved 80% accuracy with RNNs and LSTMs. They felt that knowing the winning streak of a team and with that, a pattern of their results would help improve the accuracy. Furthermore, it allowed us to make use of the home and away team’s “history” of results leading up to the game, to an extent mimicking the effect of RNNs. Though we did not use an RNN, we constructed these datapoints to work in a similar way to how RNN’s consider the history of data.

For our validation set, we used the last 10% of matches from our dataset. Since our ultimate goal was to predict this season’s matches, we felt that it would be appropriate to build the validation set in this way.

Thus, our various different sets of datapoints allowed us to build multiple different models and perform different sets of analysis.

Discussion and Results

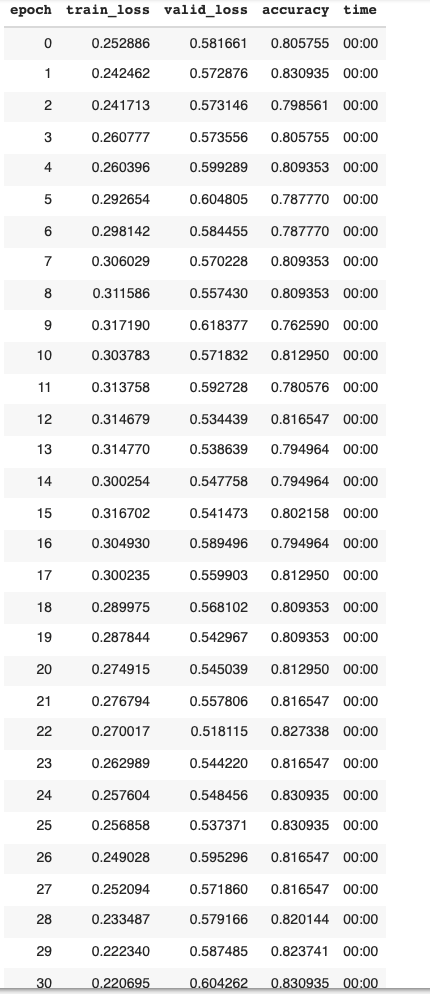

Primary Model

Our primary model was trained on input data given by several basic datapoints of previous EPL matches. These included the names of the home and away team and their current win or loss streaks. An extra column was included to denote if either team was on at least a three game win streak or not. The results of the match (win, loss, or draw) was used as our dependent variable, thus training our model to predict such outcomes of a given match. After training on eight seasons of matches (the 2014-2022 EPL seasons) throughout 15 epochs (with a batch size of 30), our model was able to produce an accurate prediction of a given match result up to 75% of the time.

Training again using 60 epochs increased the accuracy up to 78% of the time. By decreasing the batch size from 30 to 15, several more points of accuracy were obtained consistently, resulting in a final accuracy of up to 81.65%.

No further adjustments in batch size or number of epochs resulted in an increase in the prediction accuracy. These results match up closely with those of the study done by Sarika et al. This is fairly unsurprising given that the training data and provided inputs were the same for both models. Similar to the Sarika et al. study, we found that a batch size of around 30 was optimal to maximize our model’s prediction accuracy. From here we attempted to increase accuracy by adjusting the input parameters to include the name of the referee to account for potential bias and/or correlation between the arbiter of a given match and its outcome. Including this extra parameter ended up having little effect on the model as the average prediction accuracy leveled around 80%. This suggests that there is little to no correlation between the result of a match and the arbiter who oversaw it–an unsurprising and reassuring outcome. Given our success in producing a network that reached accuracies of previous studies, we moved forward by considering as inputs the predictions of several betting companies in order to provide insight into their effects on (and/or correlation with) premier league match outcomes.

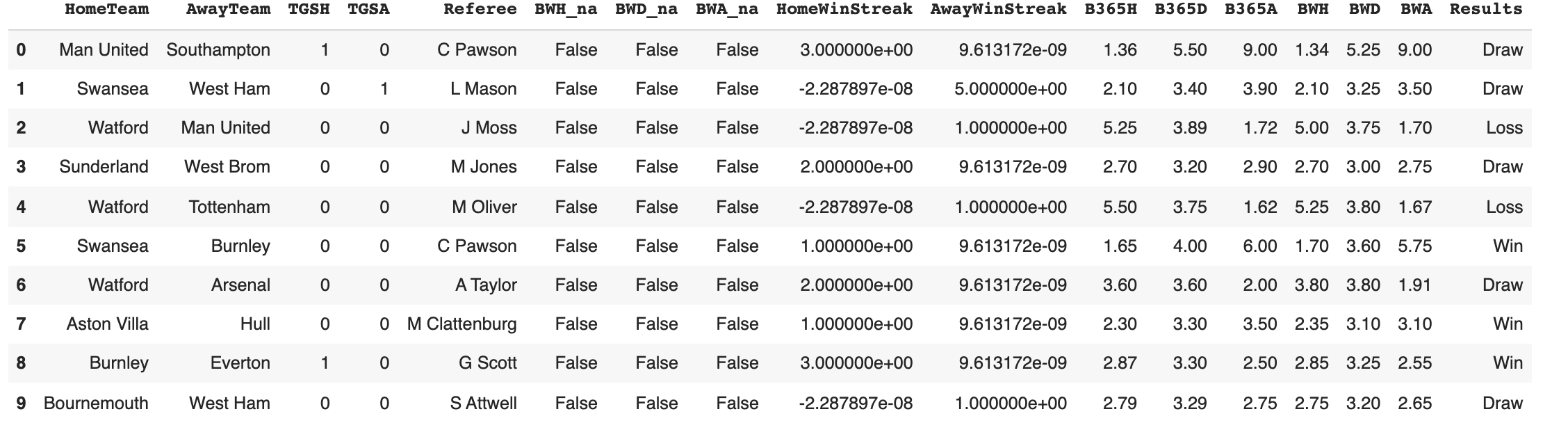

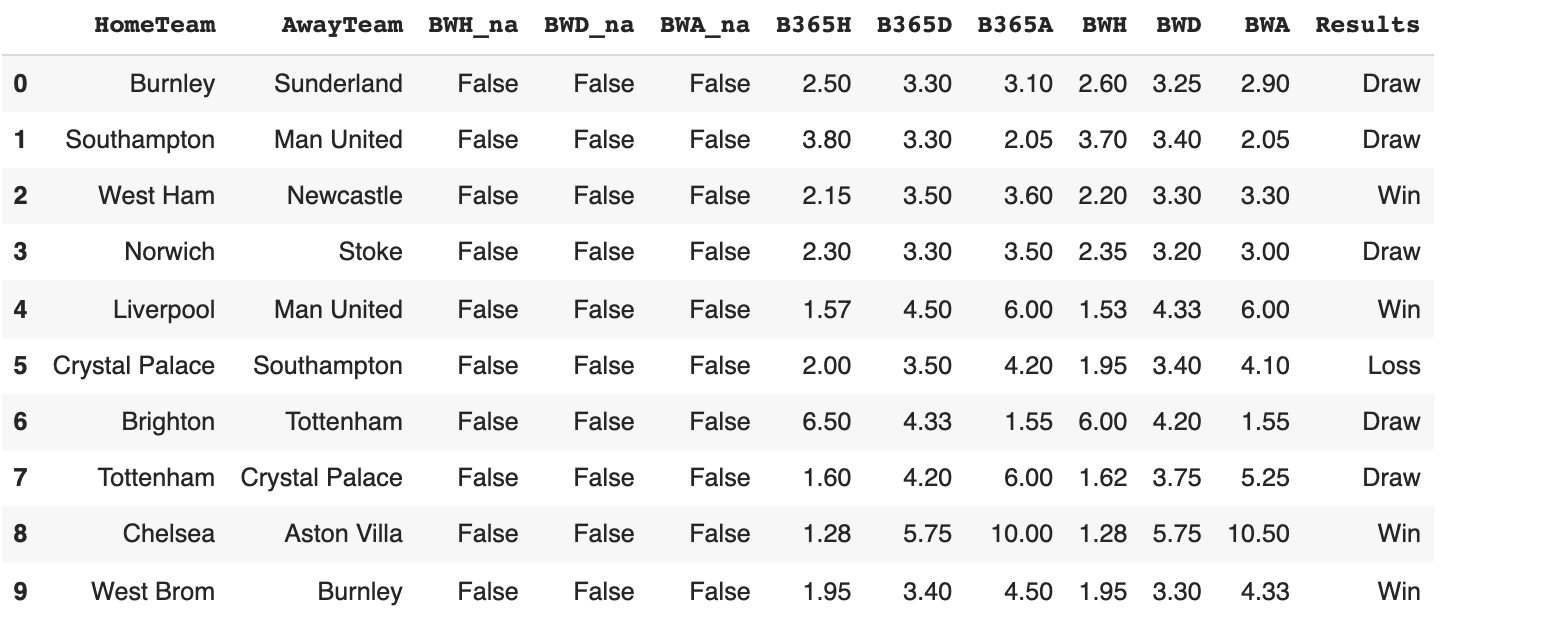

Including Odds Data

By including the predictions made by different betting organizations, our model reflects the general expectation of a matches outcome by bettors. Adding predictions made by bookie odds (namely Bet365 and BetWay), the accuracy ranged between 73% - 77% and averaged around 75%. Note that the column B635H corresponds to the general consensus that the home team would win, as gathered by B365, while B365A corresponds to such odds for the away team. This is similarly the case with the BWH and BWA columns with regards to the expectations of bettors gathered by BetWay. Below is a sample batch using this data as well as the highest produced accuracy from the model.

Given the high variance in expectations made by betting organizations as well as the immense uncertainty in match outcomes, these added parameters unsurprisingly did not yield significantly different results from our initial model. Human psychology plays a large factor in the odds expressed for a given matches outcome and thus make our model more prone to humman error and bias. To complete our analysis we trained a model solely using the betting odds as inputs.

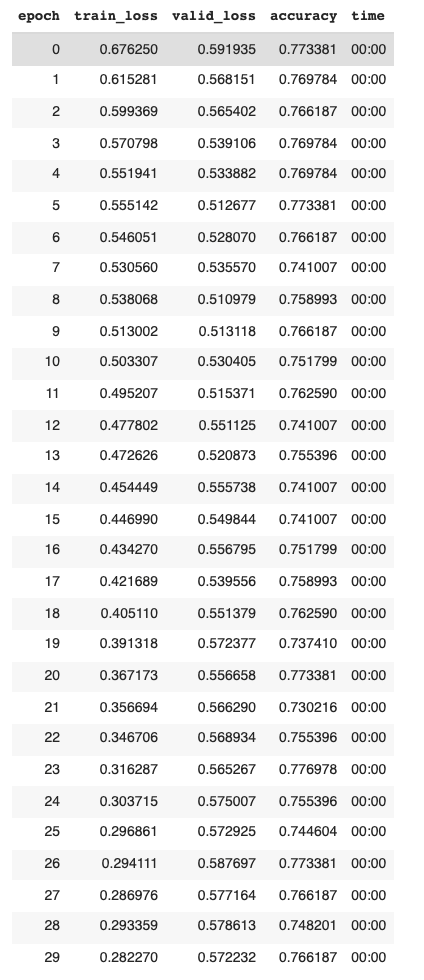

Just Using Odds Data

For the model only utilizing the predicted odds by the aforementioned betting organizations, the accuracy dropped to between 50% - 61%. This reflects that by combining the predictions from these top two betting agencies, a model is only able to accurately predict a match outcome slightly better than half of the time. By training a model on only the predictions of other programs, the prediction power of our model was significantly reduced. This speaks to the lack of substance to such a model–one that does not rely on information about past matches themselves. Below is an example training batch as well as the final accuracy of this model.

Similarly, training a model only using BetWay odds and another only using Bet365 data yielded accuracies between 50-60%. Perhaps increasing the number of betting agencies would yield different results, although this demonstrates the lack of accuracy reflected by standard betting organizations.

Varying Hyperparameters

To maximize the non-odds model’s accuracy we trained it several times, varying the hyper parameters. Primarily, the parameters that we altered were the batch size and number of epochs. We also obtained the optimal learning rate using FastAI’s lr_find() method as seen below.

On average, this gave a learning rate of around 0.00144, although it varied slightly depending on the batch size used.

Below are the accuracy results of changing the number of epochs and batch size.

| Table 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Batch size | Number of epochs | Accuracy |

| 5 | 15 | 73.02% |

| 15 | 15 | 75.89% |

| 30 | 15 | 74.82% |

| 60 | 15 | 77.69% |

| 124 | 15 | 76.25% |

| 5 | 30 | 75.19% |

| 15 | 30 | 78.77% |

| 30 | 30 | 78.77% |

| 60 | 30 | 79.13% |

| 124 | 30 | 76.62% |

| 5 | 60 | 69.24% |

| 15 | 60 | 81.65% |

| 30 | 60 | 78.05% |

| 60 | 60 | 79.49% |

| 124 | 60 | 80.21% |

The accuracy increased gradually when we increased the number of epochs up to 60. From here the accuracy tended to plateau. Increasing the batch size up to 15 yielded the most consistently accurate model. Thus, the final hyperparameters used for the model included a batch size of 15 and trained on 60 epochs. It is worthy to note that increasing the number of epochs could result in overfitting, thus resulting in our model just encoding the data (memorizing it), rather than “learning” it. Thus, we did not increase the number of epochs further even though it might have lead to higher accuracies.

Ethics Discussion

When reflecting upon the ethical angle of our project, it is important to note that our models that included betting organizations data produced results that were significantly worse than those without them. This could potentially be due to muddled incentives of such organizations as the ones we utilized in our study. These organizations have the sole incentive of increasing profits, not necessarily providing the most accurate predictions of match outcomes. Thus, including such data to train models might not only be introducing a decrease in model accuracy, but also skewed incentives of for-profit institutions. By evading the usage of betting odds, we have produced a model that is more friendly toward the consumer. While we cannot know for certain why gambling sites have slightly inaccurate predictions, we understand that by introducing more nuanced and accurate models, consumers can gain advantage over large gambling sites who make copious amounts of money. Therefore, a conventional sports better can rely less on speculation and more on data.

By building a successful model, we realise that it might lead to an increase in the amount of bets made on Premier League matches, leading to those consequences faced by excessive gambling. For one, the number of bets might drastically increase with people taking higher risks. Clearly, if people are aware of the result of the game from beforehand for about 70-80% of the time, there is a lot of money to be made. Another issue that might surface is a lack of enjoyment in watching football. If people know the result beforehand, would they still enjoy watching the game as much? These are some questions and consequences we need to be wary of before releasing such a model to the public.

Future Work

Building upon our model, we are interested in trying to replicate our success for other European soccer leagues such as La Liga in Spain or Ligue 1 in France. Furthermore, a point of interest that composed a crucial part of the model was the inclusion of a team’s winning streak. By adding winning streak data as a parameter, we might be able to successfully craft a general model that can be significantly more sucessful than current betting algorithms through utilizing data pertaining to a team’s momentum. There are so many potential factors that go into a match’s outcome that it is impossible to define and encode all of them in a neural network. In the future we hope to identify some of these that are lesser known or that have a greater bearing on match outcomes.

Reflection

Based on our results, we observed that historical data, especially a team’s win streak, is key in predicting the outcome of future matches. However, it is not always wise to rely solely on historical data. For a test example, we used our model to predict the match outcome between Chelsea and Man United, played on 28th November. Our model predicted a win for Chelsea, who had a significant winning streak advantage before the match. In the end, the match concluded in a draw contrary to our model’s prediction. During the match Chelsea players made some human errors, and Man United’s interim team coach opted for an ultra defensive approach on the day. All these factors weighed heavily on the final scoreline. Even at 81% accuracy, with our limited data, it is difficult for our model to capture several other factors that determine match outcomes and must be used with precaution especially for betting purposes.

To allow interactivity with our model, we have built a simple web application to test our model on any two Premier League teams. The ‘app.py’ file in our Github repository can be run using Streamlit to interact with it.

For future work, we could potentially try building the model solely in PyTorch to perhaps gain a better understanding of the PyTorch framework. We could also try building our own datapoints and combining data from multiple other datasets to see if they have an effect on the accuracy. This would include datapoints such as expected goals scored, expected goals conceded, current position in the table and an unbeaten streak. Furthermore, building a different type/more complicated neural network might have improved our accuracy.